Noteworthy Stories for 2014

Responding to porcine epidemic diarrhea (PED), initiating the pig sales adjustment mechanism, and steadying pork prices

There was an outbreak of porcine epidemic diarrhea (PED) in October of 2013 that carried over into 2014. The epidemic was concentrated mainly in central and southern Taiwan, being most severe in January of 2014. Teams led by experts from the COA’s Bureau of Animal and Plant Health Inspection and Quarantine (BAPHIQ), industry groups, and the animal health departments of local governments simultaneously responded with bio-safety measures to deal with the situation at affected sites and to strengthen disinfection and preventive measures at critical locations. The epidemic began to abate in April of 2014.

However, besides directly causing deaths among hogs, the PED epidemic also impacted the reproductive capabilities of sows. As a result, the supply of domestically produced hogs fell by 757,000 (about 8.7%) below the level of 2013, resulting in a shortfall in the supply of domestic pork to the market. Because the market prices for hogs in Taiwan are shallow dishes in nature, even a small imbalance in supply will be reflected in sharp price changes.

To ensure that price fluctuations in 2014 did not damage the development of the hog-raising industry, the profits of hog farmers, or the interests of consumers, in the middle of February of 2014, the COA requested industry associations to intensify guidance of their members for setting hogs onto the market. We also asked the Taiwan Sugar Corporation, a state-owned corporation that is a major producer of hogs, to increase their output. In addition, on March 4 of 2014, the COA established a “Hog Price Stabilization Task Force,” which adopted the following measures:

Restrictions on purchasing

With the arrival of the Chingming Festival, we gave first priority to meeting consumer demand for fresh meat. In order to uphold the interests of consumers, acting on the basis of the "Animal Industry Act," the COA announced that from March 25 to April 4, we would impose restrictions on purchasing volume at meat markets by buyers from frozen meat processing plants.

Adjustment of supply and demand

The COA kept track on a daily basis of trading in all major auction markets as well as at the sources of supply of hogs; we also requested the Taiwan Sugar Corporation and major hog-raising enterprises to cooperate in adjusting supply to specified meat markets to meet demand.

Since demand for pork always rises at holidays, prior to the Chingming Festival, in order (i) to ensure that suppliers continued to provide hogs in a normal manner and (ii) to stabilize prices at a reasonable level, the COA ceased paying insurance premiums or terminated insurance contracts for overweight hogs. At the same time, measures to increase supply were supplemented by moves to make sure that all pork coming to market was sanitary and healthy. The COA intensified sample testing at meat markets. In cases where the test results did not meet regulatory standards for veterinary-drug residues or foot-and-mouth disease antibodies, these cases were handled according to law. The COA also initiated controls over movement of hogs and strengthened supplementary vaccination.

Adjustments to consumer demand

The COA coordinated with relevant businesses, and with major institutional food consumers (such as the military and correctional institutions) to use alternative types, cuts, and amounts of meat during the pork shortage. We also acted through multiple channels to release fair-price pork to markets, and also coordinated with the poultry industry to increase production, supply, and marketing of broilers (chickens), to provide a pork substitute.

Market differentiation

Labeling for frozen meat was extended in May of 2014 to cover pork, so that consumers could more easily distinguish frozen pork and protect the market share of domestically produced fresh pork.

Special case approval of imports

The National Animal Industry Foundation undertook special importation of 2,466 metric tons of frozen pork, which was released on to the market with due account taken for its impact on relevant businesses and farmers, while protecting the interests of consumers.

Adjusting “off-duty” days at markets

This policy was implemented based on the situation with respect to the supply of hogs during holiday periods, in order to ensure a supply of meat that would meet demand during these periods.

The countries that are the main sources of pork imports for Taiwan—i.e. the US and Canada—also experienced outbreaks of PED. This resulted in a sharp increase in the international futures prices of hogs. Comparing prices at the beginning of the year with those of the greatest fluctuation, hog prices in Taiwan rose (at the highest point) by 27%. In comparison, in Tokyo the price of hogs rose by as much as 35%, in the US by 66%, and in Canada by 60%. Clearly the price increase in Taiwan was much more moderate than in these countries, indicating that the measures adopted by the COA achieved the policy goals of ensuring a reliable supply of pork at fairly stable prices, while also taking into account the interests and profits of farmers.

Termination of state purchasing of rice cultivated by ratooning

With liberalization in international trade, Taiwan must keep improving the quality of its rice in order to satisfy domestic consumers. We must adjust the domestic rice cultivation structure and establish a system for cultivation of superior rice.

Some farmers choose to grow rice using a convenient but inferior process called “ratooning” for the second crop of each year in coastal areas in northern, central, and southern Taiwan. This involves leaving the root of the rice plant in the ground during the first harvest, avoiding the need to transplant new rice seedlings. The COA wishes to discourage cultivation of this inferior ratoon rice. Therefore, on November 14 of 2013 the COA announced that starting from the second growing season of 2014, the government would no longer purchase ratoon rice for state stocks, in order to create a disincentive for farmers to grow it, and a corresponding incentive to grow higher quality rice.

In fact, the COA wishes to generally discourage two-season rice cultivation, and therefore we are also promoting “single-season rice cultivation.” This policy should raise the quality of domestically produced rice while have the side effects of maintaining balance between supply and demand for rice and bolstering farmers’ incomes and profits.

To return specifically to ratoon rice, in fact this type of rice—which is produced only in small amounts and whose production volume is unpredictable and unstable—has never been much sought after in the market by private-sector buyers, because it is of low quality when harvested, and becomes even worse during the drying process. It is also undesirable because it has a high loss rate during processing, damaging farmers’ incomes. Finally, it is especially vulnerable to disease, which not only reduces production volume and raises the costs farmers must invest to protect it, it endangers the neighboring cultivation environment.

For these reasons the COA has been guiding farmers to abandon this type of rice (which is grown in the second growing season only) and cultivate higher quality rice in only one growing season per year (the first), while cultivating other types of crops in the second. These preferred second-season alternatives fall within three categories. The first category is crops grown under contract for specific buyers that will produce more income for farmers, and includes (i) import substitution crops, (ii) crops with export potential, and (iii) unique local niche crops. The second is crops of a scenic nature (like the so-called “sea of flowers”) that will improve local scenery and contribute to the rural leisure industry. The third is green-fertilizer crops.

To encourage farmers to switch to these alternatives, and to grow rice only during the first growing season, the COA has extended the period during which farmers can apply for subsidies for transition to these alternatives, in order to make it easier and more attractive for farmers to cooperate with the policy. Subsidies are as follows:

● For transition to contract crops: Each Agricultural Research and Extension Station in its jurisdiction acts on the principle of “suitable crops for suitable land” and guides farmers in the selection and cultivation of import substitution crops, crops with export potential, and unique local niche crops. Subsidies ranging from NT$22,000 to NT$45,000 per hectare are available depending upon the type of crop.

● For cultivation of scenic plants: The COA encourages cultivation of aesthetically appealing plant life because this can contribute to the development of the local tourism industry (especially attracting people who come specifically to see these scenic crops), as well as have innate aesthetic benefits for the local community that can enliven their village economies as well. Subsidies of NT$45,000 per hectare are available, and in addition the government provides the seeds for these crops.

● For growing “green fertilizer” crops: The COA has been working to “transplant” the successful experience that Yilan County has had in promoting the policy of cultivating rice only in the first growing season of the year while growing green-fertilizer crops in the second growing season. Cultivation of such crops increases the fertility of the soil and improves its physical and chemical properties. Improvement of the soil is beneficial to the growth of the crops raised in the following season, and reduces the need for manmade fertilizers. Subsidies of NT$45,000 per hectare are available.

● To encourage farmers to cooperate with these measures, the COA has opened “demonstration farms” to visitors and held many explanatory meetings. In the second growing season of 2014, research and extensions stations operated 61 demonstration farms for transition to contract crops; these farms were open to hands-on visits by farmers. The COA also held more than 200 explanatory meetings, and issued explanatory materials more than 900 times through the electronic and print media. We also printed posters and pamphlets in the popular “for dummies” format, and also utilized local broadcasting systems and extension networks to reach out to both farmers and the general public.

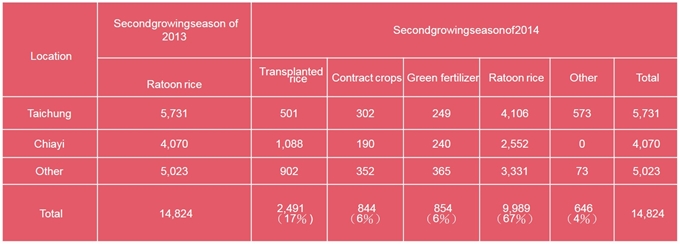

As a result of these incentives and efforts, the cultivated area of ratoon rice in 2014 fell to 9,989 hectares, 4,835 fewer than in 2013 (14,824 hectares), a reduction of 33%. We will continue to encourage farmers who still cultivate ratoon rice to switch to high-quality rice in one season only, and to transition during the second growing season of each year to one of the various alternatives, with the specific choice depending upon local conditions. These policies will raise the competitiveness of domestically produced rice and protect the incomes and profits of farmers.

Table: Progress in reducing ratoon rice cultivation, 2013 vs. 2014

Strengthening feed oil controls, ensuring food safety for citizens

The feed oil scandal: origins and investigations

On September 4 of 2014, the media reported that a company called Ching Wei had purchased subpar oil, manufactured using gutter oil and waste oil from leather tannery plants, from a businessman in Pingtung named Kuo, and that they used this oil in making animal feed. The COA immediately asked the Pingtung County government to investigate, and the COA independently collected other evidence, in order to gain a full understanding of the oil supply and distribution chain. At the same time, local governments with jurisdiction immediately sealed the warehouses where oil made by Ching Wei, as well as by any downstream companies supplied by Ching Wei, was stored, and collected samples for testing.

Although the tests indicated that the oil conformed to not only ROC standards for oil used as an ingredient in animal feed, but also to the standards of the European Union, because the precise sources of the oil were unclear and the mixture was adulterated, the COA asked businesses to self-enforce standards above and beyond the minimum requirements, and to destroy all questionable oil. Questionable oil was sent back to Ching Wei where it was sealed and stored until it was destroyed with the assistance of the Environmental Protection Bureau of the Kaohsiung City government.

In September of 2014, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of the Ministry of Health and Welfare investigated oil products imported from a Vietnamese company called Dai Hanh Phuc by a Taiwan firm called Ting Hsin International Group, checking especially its compliance with law and whether it was suitable for human consumption. The FDA discovered that the oil products exported by Dai Hanh Phuc could only be used for animal feed, not for cooking oil used for human consumption. This immediately raised widespread concerns among the public and media about where the oil exported by Dai Hanh Phuc went to and how it was used, and many doubts were raised that businesses were mixing together oil suitable only for making animal feed with cooking oil intended for human consumption. Government agencies immediately began studying measures to strengthen controls over imported oils and fats. In addition, the government traced what happened to all the oil imported under the 1518/3823 code number, and handed over cases of illegal actions by businesses to prosecutorial agencies for further action. Meanwhile, the COA tracked all the oil imported for use in making animal feed for the period from January through August of 2014, and investigated nine firms that had imported oil not suitable for human consumption from Dai Hanh Phuc at any time since 2011. It was discovered that six of the firms had supplied 7,698 metric tons of imported oil to makers of animal feed, while Ting Hsin imported 4,726 metric tons and another firm, Yung Cheng Oil Company (including its subsidiaries) imported 29,873 metric tons.

With judicial investigations of these firms already underway, the COA asked investigators to provide us with further data. However, given that the paper trail for the import and sale of questionable oil was not complete, and the sourcing of oil used by these companies was complex, there was no hard evidence based on which we could determine exactly where oil imported from Dai Hanh Phuc ended up.

Therefore the COA decided to approach the problem from the opposite direction. We investigated the volume of oil used by downstream animal-feed makers and the data recording their trading in oil, to try to reconstruct a paper trail. We concluded that 97% of the oil imported by Yung Chung was resold for the manufacture of animal feed. In addition, we found that the total volume of oil purchased by downstream animal-feed makers from Ting Hsin exceeded Ting Hsin’s total volume of imported oil not for human consumption, which suggested that the oil imported by Ting Hsin from Dai Hanh Phuc was probably supplied (or mostly supplied) for the purposes of making animal feed, with Ting Hsin also buying oil from other suppliers to supply to animal feed makers.

Reassessment of the feed-oil control system

Prior to October 30 of 2014, feed oil did not fall under the COA's previously announced "Detailed List of Animal Feed Items." Therefore it was not necessary to have any kind of manufacturing or import certification or registration for feed-oil production, processing, packaging, or import. Also, prior to November 13 of 2014, feed oil did not fall under the COA's previously announced guidelines for inspection and testing of imported animal feed, so it did not have to go through any kind of inspection or testing to be imported. The COA had previously treated feed oil as a subject for testing only after it reached the market. Each year there was a specific plan for sample-testing feed oil for things like peroxide value (POV) or free fatty acids. This was our approach to keeping track of feed-oil quality. Therefore when the scandal broke, we had no way of knowing for certain the exact businesses involved in importing, manufacturing, and selling it. This made the task of investigating the scandal extremely complex and difficult.

The COA will change the law to clearly stipulate that animal-feed makers shall keep detailed records of their suppliers and ingredients as well as paper trails of where their products go, so that the entire trail of ingredients and finished products can be tracked. We have drafted amendments to several provisions of the “Feed Control Act” to provide the legal basis for future regulatory action as well as higher fines for violators.

Measures to control at the source and upgrade traceability

In response to the adulterated-oil scandal, the COA took a number of measures to upgrade controls and regulation. On October 30 of 2014, we announced amendments to the “Detailed List of Animal Feed Items” that added “animal oils and fats” and “plant oils” to the list. Also, starting on October 31, we began implementing comprehensive separate-track management of imported oils, with a requirement that feed oil must have a permit from the COA and monthly reports must be filed of the sources, movements, and destination of feed oil. And on November 14 of 2014 we began implementing border inspections.

Also, starting from January 1 of 2015, domestic feed-oil makers must get animal-feed manufacturing certifications. Only then will they be allowed to manufacture or process feed oil, or to separate and package feed oil. Also, we are pro-actively promoting amendments to the “Feed Control Act” and strengthening existing animal-feed control regulations, in order to have the legal framework in place that will allow us to construct a comprehensive system for: (i) control of animal-feed sources and (ii) traceability of animal feed and its ingredients. These measures will allow us to uphold the safety and sanitation of animal feed and livestock products, ensure the safety of the food citizens consume, and rebuild consumer confidence.

A highly successful year for the grouper and saury fishing industries

The comprehensive recovery and growth of the grouper industry

Taiwan enjoys a number of innate advantages for its grouper aquaculture industry, including a suitable climate, mastery of reproductive technology and techniques, and proximity to major markets. In October of 2009, when the Executive Yuan (cabinet) approved a long-range plan for “Excellence in Agriculture,” a program was incorporated into this plan to assist the aquaculture industry to recover from the severe damage caused by Typhoon Morakot. A target was set to double the value of the industry to NT$7.6 billion by 2015. Following the adoption of the plan, the government started the right to work to rebuild the aquaculture industry, and shipments resumed in November of 2010. In addition, the government has, in cooperation with industry and academia, working through a variety of channels—policy adjustments, improving the aquaculture production environment, technological R&D, marketing—to undertake the following tasks:

● Opening of direct shipment to mainland China of live grouper, incentives for construction of high-efficiency live-fish transport ships, development of sales channels.

● Inclusion of provisions in the Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement with mainland China (signed in June of 2010) that lower import duties on grouper to zero.

● Promotion of policies to lower production costs and increase competitiveness, including: (i) use of high- efficiency man-made feed for grouper, (ii) construction of superior-quality fry-breeding facilities for grouper, and (iii) lowering of import tariffs on fresh chum used as grouper feed.

● Construction of infrastructure such as: (i) systems to deliver seawater to aquaculture ponds, and (ii) water delivery and drainage channels.

● Upgrading of production quality through measures such as: (i) development of the world’s first vaccine for grouper iridovirus, (ii) provision of veterinary services on-site at production locations, and (iii) teaching of proper methods and concepts of disease prevention and the use of veterinary drugs.

● Development of the domestic market by measures that include: (i) brokering of agreements between supermarkets and specialized processing plants to develop and market frozen grouper, and (ii) promotion of grouper as a dish at annual end-of-year company banquets and for sale in special Chinese New Year gift packages.

In 2014, the value of production in the grouper industry was NT$8.45 billion, well ahead of schedule of the 2015 target of NT$7.6 billion. Exports of grouper to mainland China, which were at 4,171 metric tons (worth NT$1.4 billion) in 2009 prior to the implementation of the aquaculture recovery and development plan, reached 17,969 metric tons (worth NT$5.88 billion) in 2014. In the future, we will continue to work to improve the production environment, develop faster and more convenient sales channels, and develop a worldwide market for our grouper, so that the industry can continue to grow in a sustainable manner.

Taiwan's world-leading Pacific saury industry

One of the major fishing industries in Taiwan is the combined squid/Pacific saury industry. It consists of a single fleet of boats, which are equipped for catching squid for part of the year, then refitted for catching Pacific saury for the rest of the year. In our efforts to upgrade the competitiveness of our squid/ saury industry, we began with amending relevant laws, regulations, and measures.

New policies in 2014 included the following: (a) We began permitting fishing boats and transshipment ships from Taiwan to offload saury catch at the Port of Busan in Korea. (b) We announced that in cases where the gap between the catch reports and the approved sales volume is lower than 10%, we would simplify shipment back to Taiwan and through domestic marketing channels for specially designated sectors of the fishing industry for which there is no need for import permits and which are exempt from import customs duties. (c) We announced that squid/saury fishing vessels with appropriate permission can approach mainland Chinese fishing boats or dock at fishing harbors in mainland China, in order to reduce shipping costs.

The total annual catch volume of Taiwan's Pacific saury industry has exceeded 160,000 metric tons every year since 2010, and in 2014 surpassed 200,000 metric tons for the first time. This means that once again we were ahead of Japan as the world leader. In addition, following the signing with mainland China of the Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement, tariffs on exports of saury to mainland China steadily declined and are now at zero. The volume of saury exports from Taiwan to mainland China rose from 7,066 metric tons (worth US$2.87 million) in 2009 to 41,710 metric tons (worth US$26.34 million) in 2014. In the future we will actively participate in the North Pacific Fisheries Commission and similar bodies in order to uphold the rights and interests of our Pacific saury industry.